Enjoying a Lake Michigan beach this summer? Thanks may be in order to an unlikely helper — invasive quagga mussels.

New research out of Michigan State University shows Lake Michigan beach closings have dropped over the past 15 years as E. coli bacteria concentrations have dropped. That time period coincides with the explosion of quagga mussels across the Great Lakes and especially in Lake Michigan.

"It's a good thing for all of those beachgoers who are getting ready to go out this weekend," Chelsea Weiskerger, a doctoral student at MSU and co-author of the study, said Friday.

Chelsea Weiskerger, a PhD student in Michigan State's environmental engineering department, samples lakebed sediments at a Lake Michigan beach in Indiana to conduct bacterial analysis for E. coli on the sand in the fall of 2016. (Photo: Chelsea Weiskerger)

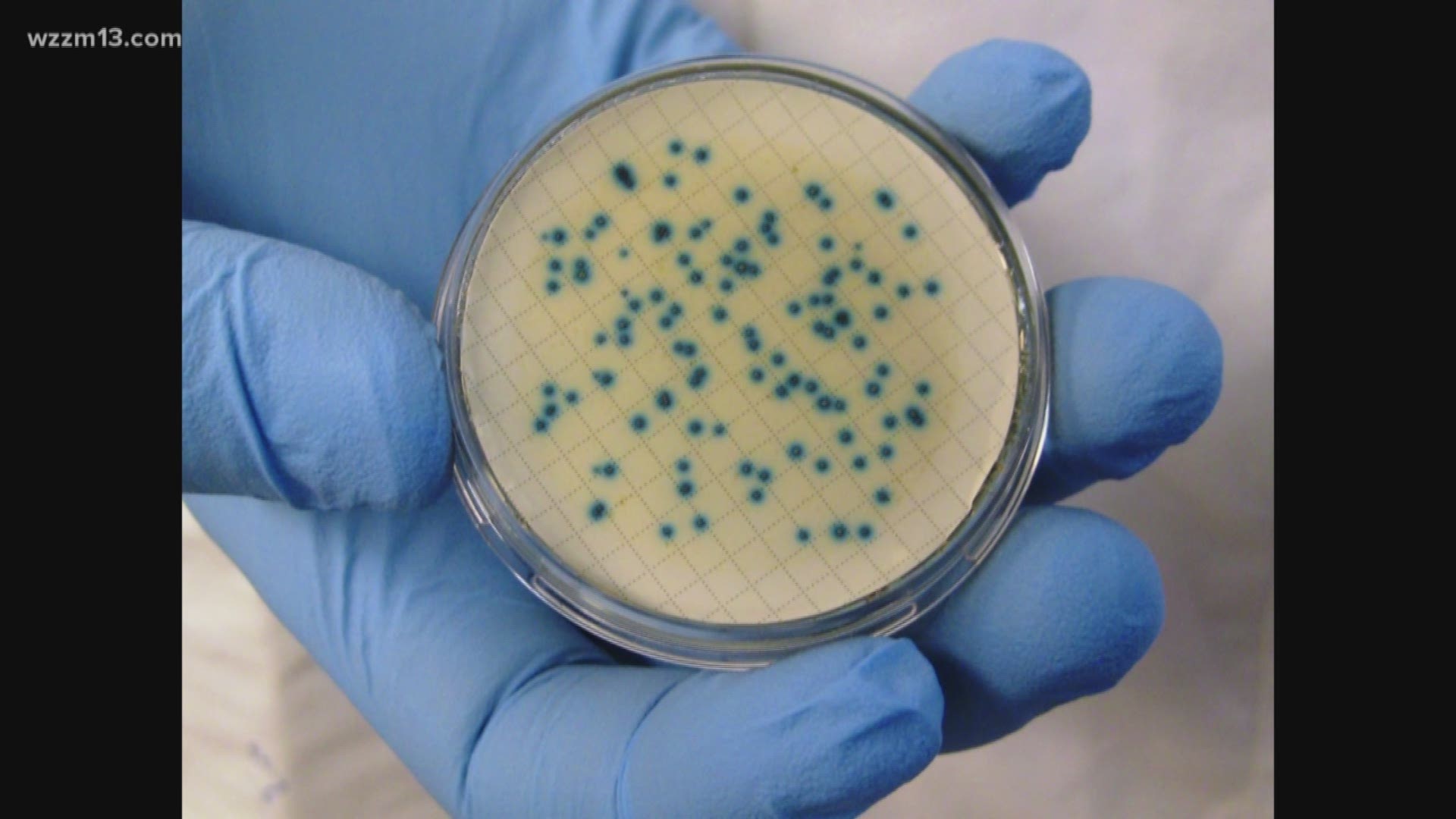

E. coli, a bacteria from the digestive tracts of both animals and humans, is associated with fecal contamination, and used by public health officials as an indicator of the potential presence of other bacteria that can make people sick with diseases such as dysentery, cholera and typhoid. When E. coli counts are too high on beaches, they're often closed.

That's where the quagga mussels come in. Almost three decades after being discovered in Lake St. Clair, likely arriving in the ballast water of freighters that traveled through eastern Europe, quagga mussels can now be abundantly found in each of the Great Lakes and most major river systems in the eastern U.S. Though only about the size of a dime, the mussels reproduce quickly, eat voraciously and clump together, clinging to almost anything in the water.

Quagga mussels now cover much of the Lake Michigan bottom, and its their immense amount of filtration that is reducing E. coli counts.

"We think their input might be twofold: They might directly filter out the E. coli from the water, and by making the water clearer, they allow the sunlight to come in and deactivate the bacteria," Weiskerger said.

From 2000 to 2014, median water clarity in Lake Michigan increased 32%; median E. coli concentrations decreased by 34.9%, and, of 45 Lake Michigan beaches studied, 42 showed a relative decrease in E. coli from pre-2007 levels, the study found.

But couldn't the results come from reductions in sewage and other E. coli contributors reaching the lake? Weiskerger and her study co-author, U.S. Geological Survey retiree Richard Whitman, compared the Lake Michigan results to Lake Erie, where quagga mussels are also abundant but where nutrient loads contribute to algae blooms and less water clarity.

"Lake Erie is showing the opposite trend in comparison to Lake Michigan, with E. coli concentrations and beach advisories rising," she said. "The difference is Lake Michigan has been becoming clearer in recent years, and that's been attributed to a lot of the filtering of the quagga mussels."

Weiskerger's research was published last month online in the scientific journal Science of the Total Environment.

Though her research focused primarily on the western side of Lake Michigan, and beaches in Wisconsin, around Chicago and northwestern Indiana, "we would probably see the same trends on the other side of Lake Michigan," she said.

Dan Thorell, environmental health director at the Grand Traverse County Health Department, who monitors water quality at the county's beaches, said E. coli hasn't been enough of a problem there to know how much of an impact quagga mussels are having, without diving into the data. But Weiskerger's findings "seem logical," he said.

"Quagga mussels have proliferated, they clear up the water, which allows more sunlight, and the UV rays will kill the E. coli," he said.

"I used to work in Genesee County. The Flint, Shiawassee and even the Saginaw rivers were the color of chocolate milk all the time. Heavy clay soils and all that sediment clouds the sunlight. If there's E. coli there, it's going to survive longer."

Quagga mussels' help on E. coli doesn't make them good guys for the Great Lakes, said Tammy Newcomb, senior water policy adviser for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

"The food web destruction that has happened as a result of the way they filter everything out of the water — the small algae the zooplankton eat, that the small fish need —" has unquestionably harmed the Great Lakes ecosystem, she said.

"They've been detrimental to native mussel fauna as well. And shell-littered beaches are dangerous for children's feet."

Weiskerger said her study is one of the first looks at long-range E. coli dynamics on the Great Lakes — contamination that's typically looked at on a short-term or seasonal basis.

"It's a highly complex and very dynamic system, with lots of issues to look at," she said. "This is the first task we've done for this, and we got some very interesting results."

Contact Keith Matheny: 313-222-5021 or kmatheny@freepress.com. Follow on Twitter @keithmatheny.

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the WZZM 13 app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@wzzm13.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter.